Where are the workers? Demographics driving labor shortage

Age demographics are one of the greatest drivers of the ongoing labor shortage.

Idaho's labor market was sailing along for years, steadily hovering in an equilibrium where the number of job openings and unemployed residents was closely parallel.

“Then in 2022, we start to run into a problem, and the problem is that we can’t create jobs at the pace we used to because we’re having a hard time filling those jobs,” said Sam Wolkenhauer, labor economist with the Idaho Department of Labor. "We have essentially exhausted most of the available labor, and we’ve reached a point where Idaho businesses can continue to create jobs, but it’s going to prove very, very difficult to fill those jobs."

Wolkenhauer presented a close look at Idaho's labor market Dec. 6 during an online webinar, “Generations in the Workforce."

He identified structural changes that affect Idaho's economy and that are expected to have long-term impacts on the way the economy functions.

The market began to unravel when the COVID-19 pandemic struck, creating a huge, but temporary, spike in unemployed residents.

After COVID, a problem began to surface — a labor shortage.

"The number of open jobs in Idaho begins to pile up," Wolkenhauer said. "Pre-pandemic, we had maybe 20,000 open jobs at any given time. Today, it's well over three times that number, and it certainly far exceeds the number of people available to fill those jobs."

The shortage is evidenced throughout the community, in long wait times, "help wanted" signs and businesses cutting back on operating hours, as well as the amount of people switching jobs to receive an astonishing average of 9% wage gains.

"Hiring managers, they're getting more and more desperate," Wolkenhauer said. "They're throwing bigger and bigger offer sheets trying to coax people over."

Skill level mismatch, disabilities of despair — drug abuse, alcohol abuse and depression — and child care availability have all contributed to the labor shortage, as well as early retirements.

The central problem?

"The demographics are quite bad right now," Wolkenhauer said. "Demographics are really hindering labor availability."

He used China as an example of a country suffering from demographic challenges largely due to its decades-long one-child policy.

"China is a good illustration of unstable demographics. They're aging very quickly. What do you think is going to happen to the Chinese labor force as their population shrinks?" he said. "They are of course going to have ubiquitous labor shortages, and they're already really struggling with this. China's labor force hit its high about three years ago and it's begun to shrink pretty quickly."

In the U.S., the number of prime-age workers between 25 and 54 is starting to decline. It was stable from about 1980 to 2020, but as the second-largest generation of 71 million — the baby boomers, born between 1946 and 1964 — retires, the "Goldilocks" era of labor is coming to an end.

Boomers grew up with an average of three siblings and gave the workforce a huge boost as they became working age.

"Four children per family, the workforce is going to double in size during that handoff from parent to child," Wolkenhauer said. "In the case of the boomers, it more than doubled because the boomers were the first generation where a majority of women were working as well."

Wolkenhauer said coincidentally, 2022 is the year where society is exactly halfway through the baby boomer retirement — half are retired, half are still working.

Succeeding the boomers is Generation X, a smaller generation between 40 and 55 that is continuing to work.

Millennials, or Generation Y, are the children of the many baby boomers. They comprise the largest generation at 72 million.

Wolkenhauer said the gap between the boomers and millennials is important.

"The gap suggests that we would have a limited window of opportunity where both of the big generations are working at the same time," he said. "We can think of this as a demographic 'Goldilocks' zone. We would get to double-dip on both of the big generations."

Following the millennial generation is the 67 million who comprise Gen Z, born from 1997 to 2012.

Idaho has a shortage of millennials and is one of the youngest states in the nation.

"We're almost too young," Wolkenhauer said. "Over the last 10-15 years, we had a portion of our millennials skimmed off the top. They moved to other states to go to school and to work... That means fewer young workers."

Offsetting that has been people moving to Idaho to start families. Coupled with healthy, wealthy retirees moving to the area, the demand for services far outweighs the supply of labor.

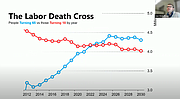

It's a phenomenon Wolkenhauer calls the "Labor Death Cross."

"How many people turned 65 this year, and how many people turned 18?" he said. "There is an in and outflow of the working age population. It's kind of like a conveyor belt: Every year, the 65-year-olds, most of them, go out and the 18-year-olds come in and it repeats every year, like clockwork because we all age at the same rate, one year at a time."

However, as of 2022, more people are going out than are coming in. The '20s is the first decade in recent memory, so far, to have a negative working population growth.

"And just based on our demographic shape, that is going to be the case for the foreseeable future," Wolkenhauer said. "We're fighting against the brute reality of time, so to speak. Every year, more people are going to turn 65 than 18, and the labor force is going to be shrinking in the face of demographic decline."