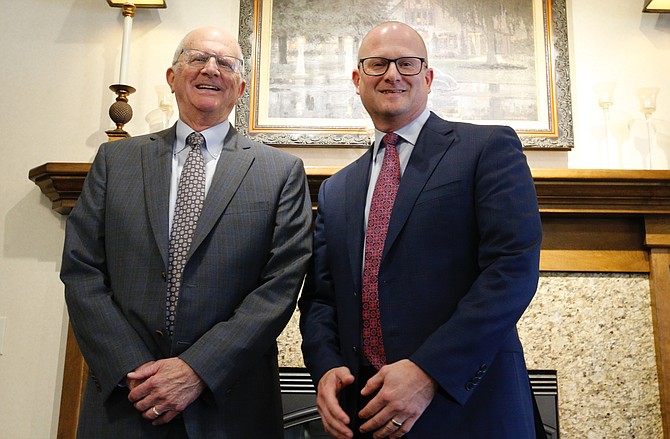

Three generations of care

Dexter and Eli Yates stand in the lobby of Yates Funeral Homes in Coeur d’Alene. The original building was Dexter’s childhood home.

COEUR d’ALENE — For 72 years and across three generations, Yates Funeral Homes have cared for Kootenai County families during their most painful times.

For Dexter and Eli Yates, the father and son who still work side by side, it’s more than a career. It’s a calling.

A ministry, as Dexter puts it.

His father, Gilbert, began his career as a funeral director at Cassidy Funeral Home in Coeur d’Alene and went on to found Yates Funeral Home at its present location on Fourth Street. At that time, an ambulance service also operated out of the facility; the phone number was 123.

Dexter grew up above the funeral home, but as a child, he hardly knew it. Neighborhood kids often came over to play in the yard or inside the house.

“My father never involved me with what was going on,” he said.

He was a junior in college, studying music, when he felt the pull to his father’s work. After earning a bachelor’s degree in mortuary science from the University of Minnesota and a tour of duty in the Navy, Dexter came home to Coeur d’Alene and began working alongside his dad.

“He said there could only be one quarterback on the team,” Dexter said of his father. “He was the boss and when I thought I could be the boss, I let him know and he stepped aside.”

Like his father Dexter, Eli Yates knew little of the family business while he was growing up. Though he didn’t know exactly what they did for work, he knew his dad and father were greatly respected. Teachers, coaches and other adults in his life often told him how much Gilbert and Dexter had helped them during their most difficult times.

“That’s what sparked my interest in becoming a funeral director,” Eli said.

He was a senior in high school when he announced that he wanted to pursue that career. But his dad and granddad wanted him to get experience elsewhere to make sure it was the right path for him.

Before attending the Cincinnati College of Mortuary Science, the same college from which his grandfather graduated, Eli completed an internship at a funeral home in Boise.

“It was the best thing that could’ve happened,” he said.

Dexter said he hadn’t expected his son to follow in his footsteps but was glad when it happened.

“I was really proud,” he said.

His own graduating class was a mix of students who came from a line of funeral directors, some of whom felt pressured into continuing the family business, and people who had spent years in other careers before they felt called to work with the dead.

Today, the father and son share an office where the walls are decorated with photos from the past, including a photo of the original funeral home building, before it was remodeled and expanded in the early 1970s.

The adjoining room was Dexter’s childhood bedroom. Behind Eli’s desk is an array of thank-you cards, a small fraction of the ones he’s received from families over the years.

Whether a fourth generation will carry on the business remains to be seen. Eli has two children who are in high school.

“There’s a lot of time in their lives to make that decision,” he said.

Over the decades, the landscape has shifted somewhat for funeral directors. The technology has changed; video tributes are now a common part of services, for example.

Families have changed somewhat, too. Blended families are more common than they once were, as are families with relatives are spread out across the country.

When Dexter got his start, most families had some experience with death. They knew what to do when a death occurred and usually knew what they wanted in terms of a service.

Dexter recalled his first house call with his father, after a man died at home in Coeur d’Alene. When the Yates arrived, the man’s widow hurried onto the porch and threw her arms around Gil.

“Everything’s going to be all right,” she said, relieved. “Mr. Yates is here.”

There was a sense of calm after that.

With life spans increasing and medicine becoming more advanced, many people are less familiar with death than they were in the past and may be well into adulthood before they experience bereavement. Today’s society is one where many people are reluctant to talk about death. That means funeral directors have to educate grieving families about the options available to them.

At Yates, funeral directors learn about the different cultural and religious backgrounds of the families who come to them so they can meet them where they are.

“We have to adapt to the people who walk through the door,” Eli said. “Being able to adapt is the best thing.”

Seeing the deceased is an important part of the grieving process for many people. Eli and Dexter strongly encourage families to consider a viewing of their deceased loved one, not only for the sake of surviving relatives, but also to give friends, colleagues and others in the community a chance to say goodbye.

“I think services and viewings help facilitate grieving,” Eli said. “If you can’t grieve, you can’t mourn and if you can’t mourn, you’re in trouble.”

The same goes for children, who are often left out of viewings or services by well-meaning adults who want to shield them from death.

“A lot of people want to take that away from children especially,” Dexter said.

But it’s important to let children decide if they want to take part, rather than make the decision for them. Given the option, many will choose to see their deceased loved one.

“The kids are more comfortable than you are,” Eli said.

Some people are reluctant or afraid to see their loved one after death. This is often because they have memories of the last time they saw the deceased—in the hospital, weakened and ill—or because they don’t want to see their loved one in an unrecognizable state.

“They don’t know how we can make their loved one look normal,” Eli said.

Working with the deceased and bereaved is as much a calling for the other staff of Yates Funeral Home as it is for Eli and Dexter. They described employees offering to come in on a day off for a service because they had developed a connection with a grieving family and wanted to see it through.

“Without our staff, we’d be nothing,” Eli said.

Each family’s situation is different.

Not just different, Dexter added, but special. He and his son treat each family with great care and carry with them three generations of knowledge.

“Our goal is to make every family feel like they’re the only ones who’ve lost a loved one,” Eli said.